A Drummer's Testament: chapter outlines and links

<Home page>

<Home page>

Volume I: THE WORK OF DRUMMING

Part 3: MUSIC AND DANCING IN COMMUNITY LIFE

Chapter titles above go to chapter outlines on this page.

Chapter title links in the outline sections below go to chapter portals.

Outline section links go to web chapter sections.

<top of page>

Volume I Part 3: Music and Dancing in Community Life

Why Dagbamba like proverbs; what proverbs add to living; how to understand proverbs; how people use proverbs as names; proverbial names and “praising”; introduction to the family; how drummers beat praise-names on their drums; where and how drumers use praise-names; the role of praising at community gathering; introduction to praise-names and dance beats

Introduction

- 1. drummers use sense to use proverbs for praise names and dances

Proverbs

- 2. their characteristics and types

- 3. meaning is not clear; doing its work involves interpreting it

Examples of proverbs and their meanings

- 4. example: “if a river is dry”: interpreting the proverb; thinking and asking

- 5. further explanation of the proverb; extended to someone with knowledge

- 6. in custom, when give a proverb, do not show its meaning; person has to interpret

- 7. why give proverbs; proverbs are two talks, different possible meanings

- 8. example: “people are talking”; two talks or meanings; good and bad

- 9. further explanation: John's reputation in Dagbon

Proverbs as indirect talk

- 10. proverbs are not straightforward; need for patience to understand the reference

- 11. indirect reference: “bury a dead goat”

- 12. “how is the market is not friendship” refers to greeting

- 13. “stealing somebody's back” reference to gossiping

- 14. “gather to bury shea nuts”

- 15. proverb has many talks inside it; don't want to say something directly

- 16. indirect talk for something you are shy to say

Proverbs make talk sweet

- 17. proverb adds to talks

- 18. proverbs give long thoughts; people like long thoughts

- 19. proverbs show people sense

- 20. the sense of proverbs can give a warning or advice; help people live correctly

- 21. proverbs are for people with sense; have to hold the meaning

Drummers and proverbs

- 22. drummers have proverbs; their sense started from worries and sadness as orphans

- 23. drummers use proverbs to praise people, as a name to fit the person

- 24. the name helps people know more about a person

Examples of praise names

- 25. example: how a proverb might apply to someone

- 26. Nama-Naa Issahaku's name

- 27. Alhaji Ibrahim's names

How praise names are beaten

- 28. name can be spoken, sung, or beaten on drum; the drum can imitate the language

- 29. many people can recognize their names when beaten on a drum

- 30. drummers learn praising; different ways to beat names; singing while beating is difficult

- 31. in addition to language, drumming has meaning in the reason why it is beaten

Learning to hear drum language

- 32. people can ask to know the meaning of the drumming

- 33. people learn to hear drumming talks to different extents; some chiefs learn it gradually; chiefs like Tolon-Naa Yakubu and Nanton-Naa Alaasani hear well because are close to drummers

- 34. chiefs can learn it as princes; befriend and sit with drummers

- 35. how a prince befriends a drummer to learn more

- 36. the prince meets the drummer quietly in the night; doesn't talk about what he learns

- 37. a prince does not show his knowledge in public

- 38. if such a prince becomes a chief, might even correct a drummer

- 39. differences among chiefs; many do not know much; elders sit near and help them

- 40. Alhaji Ibrahim wants John to learn to beat proverbs and to write down the drumming

Drumming in Hausa and Dagbani

- 41. many proverbs are beaten as names; Hausa (Taachi) and Dagbani

- 42. examples: Hausa and Dagbani versions of the same proverbs

- 43. Dagbamba proverbs that are beaten on a drum

- 44. Hausa proverbs that are beaten on a drum

The benefits of praise names

- 45. proverbial names enhance a person and also enhance the culture

- 46. a name can hold a person back; drummers will correct it

- 47. drummers praise a person with the grandfather's name; enlightening

Praise names and family

- 48. proverbs are old talks; proverbs are with everybody

- 49. drummers keep alive the names of dead people within a family

- 50. drummers know people's families; family compared to a tree

Praise names and chieftaincy

- 51. every Dagbana has a relationship to a line of chieftaincy

- 52. a commoner comes from a chieftaincy line that has separated

- 53. all Dagbamba have some relation to Yaa-Naa; even typical Dagbamba from Naa Niŋmitooni

- 54. the “children” of Naa Nyaɣsi were not all his actual children

- 55. if a prince marries a commoner, the child can become a chief

- 56. chieftaincy lines mix and separate; many ways; can go to far ancestor, like drummers to Naa Nyaɣsi

- 57. Alhaji's mother's side is Naa Siɣli; no longer a door to Yendi

- 58. everyone is a chief's grandchild; examples: Naa Zoli, Savelugu-Naa Mahami

How drummers praise within a family

- 59. when drummers praise people, they start with grandfather's name; show person's family line

- 60. praise a commoner with praise-name of a chief; all the chiefs have lines; people know to varying extents

- 61. drummers' work: praising and showing the family; makes people happy; get money as gift

- 62. family can be traced to different origins; example: Alhaji Ibrahim from Savelugu and Voggo

Praise names and knowledge of a family

- 63. drummers know a person's family to varying extents; compared to levels of schooling

- 64. people learn about their family lines from praising

- 65. praising and drumming always related to chieftaincy; chiefs and drummers are one

- 66. the old talks (history) are behind both the chieftaincy and the drumming; not written

Praising at gatherings

- 67. example: praising at a funeral house

- 68. how drummers praise people with proverbial names; excites people

- 69. example: man who killed his horse when praised

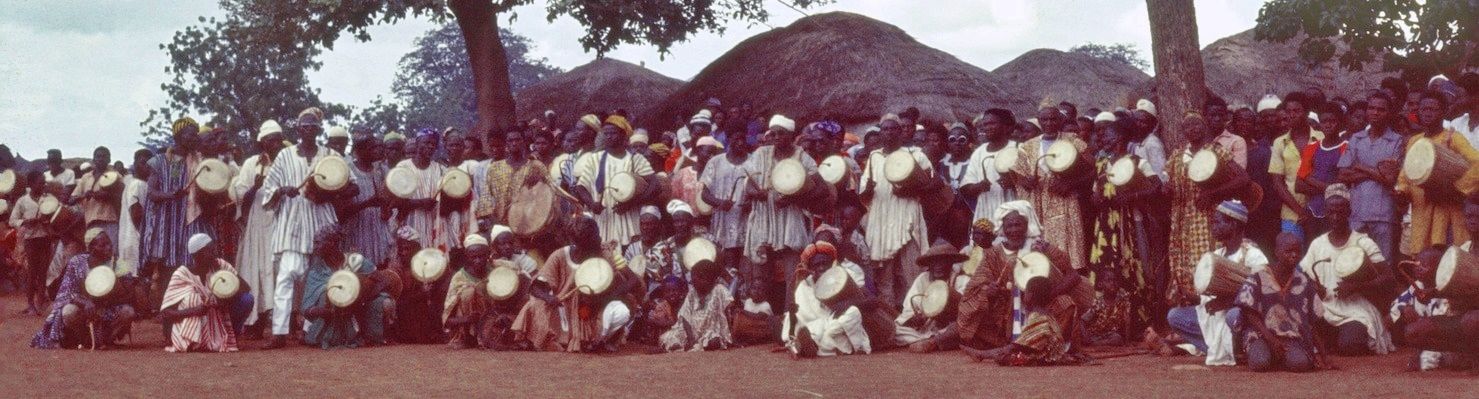

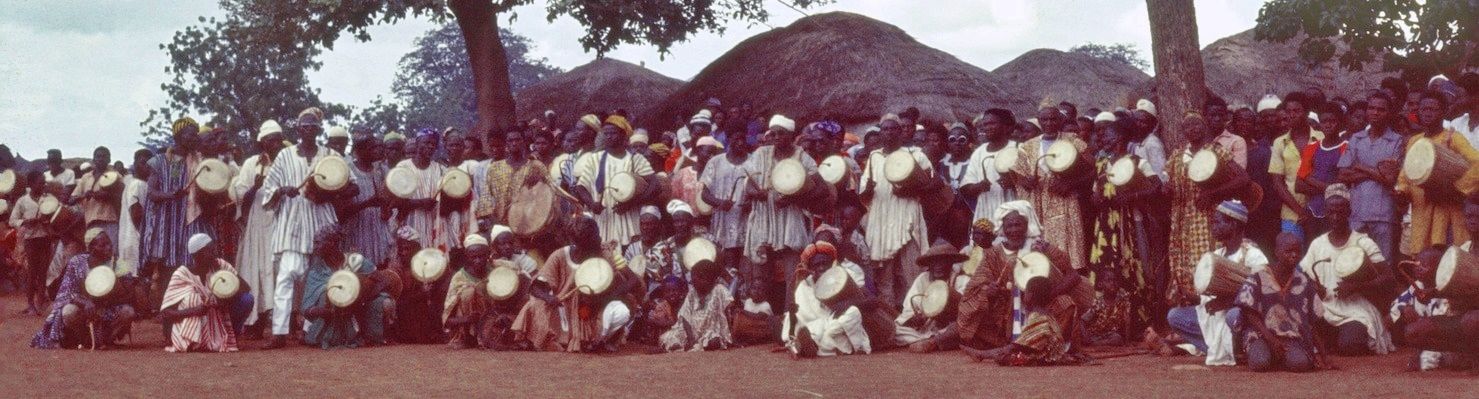

- 70. at gatherings, drummers use praise to invite people to dance; dancers receive money from friends and relatives; drummers collect it

- 71. gatherings are ways to help one another; go to funerals to support people; money makes support visible

- 72. the giving of money, from talking truths about gathers and grandfathers

- 73. people are happy at gatherings; hearing the good names of their forefathers

- 74. when drummers don't recognize someone; example: Nyohinilana Pakpɔŋ pointed out to drummers, who then praised her

- 75. people show themselves to the drummers

- 76. other people will tell the drummers about a person; this showing oneself is not like bluffing

- 77. gathering place: people get to know one another and their families

- 78. drummers also show the lower status of some people

- 79. drummers can show the high standing of a quiet or shy person

- 80. drummers show family relationships by using the same praises for different people

- 81. sometimes relatives didn't know their relationship unless drummers show them

Praising and sense

- 82. drummers find appropriate names for people

- 83. drummers use their knowledge to turn praise-drumming to dance beats

- 84. Naa Mahamadu's names

- 85. using a name for dancing; can dance to a forefather's name

- 86. drummers have a lot of sense

<top of page>

The origins of dances in chieftaincy and the drum history; examples of dances based on praise-names of former chiefs; overview: how music helps in weddings, funerals, namings, festivals; happiness and music; happiness and dancing; music as something to give to the children

Introduction

- 1. continuation of the talk about praise names

- 2. drummers use sense to turn a name to a dance

Old dances in Dagbon

- 3. Taachi: original names, without dances; from Hausa

- 4. praise-name dances are not old

- 5. dances: Zuu-waa (Tonglana Yamusah), Lua, Damba, Dikala (blacksmiths), Nakohi-waa (butchers), Gbɔŋ-waa (barbers), Baŋgumaŋa, Ʒɛm

Taachi and other dancing at former gatherings

- 6. drummers beat Taachi at gathering when Alhaji Ibrahim was young; Hausa and Dagbani names; Taachi dances now part of repertoire

- 7. formerly at funeral house: Tɔra for women, Taachi for men; children and friends arrange for the dances

- 8. women arrange for Tɔra; individual dance circle for the men, but women would also dance Kondalia and Zamanduniya

- 9. Kondalia and Zamanduniya from Hausas

- 10. some Taachi dances also from Kotokolis; guŋgɔŋ beating; drummers learned their dances

- 11. many Kotokolis lived in Tamale formerly before government made them leave

- 12. formerly only Tɔra and Taachi for funerals; Takai more for festivals; organized by Nachin-Naa

- 13. formerly Baamaaya (Tuubaaŋkpilli) not beaten at funeral houses

- 14. Jɛra only in certain towns; only at funerals of Jɛra families, or by invitation

- 15. Taachi praising like at current gatherings, but different dances; no praise-name dances

Praise names formerly were not danced

- 16. formerly the names were there but not the dances; started gradually during Naa Abudu's time

- 17. Nantoo Nimdi not danced during Naa Yakuba's times

Examples of praise names that are not danced

- 18. Naa Kulunku: Kulunku laɣim kɔbga

- 19. Naa Andani Jɛŋgbarga: Yuɣimpini

- 20. Naa Ziblim Bandamda: Kuɣa mini kasalli

- 21. some names good for beating and singing but not good for dancing; examples: Kuɣa mini kasalli

- 22. some names are beaten for horse-riding

Learning praise-name drumming

- 23. drummers learn to their extent; should not add to what they were taught

- 24. the many dances in Dagbon are because of drummers; people also have many oreferences in dancing

- 25. people tell drummers which dance they want; also, drummers adjust beating to fit the dancer

- 26. drummers usually know a dancer's preference; often follows the family

- 27. some people can dance many dances; drummers try to limit the number; after second dance, no money

- 28. some dancers change dances quickly; not a problem

- 29. differences in learnedness; a lot to learn to know details of chieftaincy and history

- 30. the dances show the history; adds to way of living

- 31. the many dances in Dagbon also come from the dancers and what they want

- 32. drummers also sing praises when beating for dancers

- 33. only some dances have singing; Damba songs not danced; sometimes songs, sometimes praise singing

Example: Naɣbiɛɣu

- 34. Naa Abilaai Naɣbiɛɣu's fighting with Bassari people

- 35. how the drummers describe such events; not always clear

- 36. Naa Abilaai killed the Bassari chief, Naɣbiɛɣu, and took his name

- 37. different ways of the story, whether Naa Abilaai or his soldiers killed Naɣbiɛɣu; no real difference

- 38. the Naɣbiɛɣu drum language and response; variations

- 39. how the Dagbani is adapted to drum language

- 40. the singing that accompanies Naɣbiɛɣu

- 41. explanation of the singing

- 42. further explanation of the metaphors in the singing

- 43. drummer will add the singing of other praise-names of Naa Abilaai

- 44. how the singing fits with the drumming and responses

- 45. the singing is not one way; many differences depending on the drummer

- 46. the dancer changes with the singing and beatingh; singing changes depending on the family of the dancer

Example: Nantoo Nimdi

- 47. Naa Yakuba's name; poisoned meat

- 48. explanation of the name

- 49. singing the different praise-names of Naa Yakuba

Example: Naanigoo

- 50. Naa Andani's name; how he called his name in the Zambarima war

- 51. the singing inside Naanigoo

- 52. explanation of the name

- 53. further explanation of the name

Example: Ʒim Taai Kurugu

- 54. Naa Alaasani; the meaning of the name

- 55. additional language inside the drumming

- 56. the origin of the name in Naa Alaasani becoming Yaa-Naa

Example: Naa Abudu

- 57. how he was made Yaa-Naa by the British

- 58. Setaŋ' kuɣli; explanation of the proverb; same name as Naa Zanjina

- 59. danced by horses in procession; wɔrbar' sochɛndi

- 60. no songs; sing the praise-names of Naa Abudu

Other chiefs' names and dances

- 61. Naa Mahama Kpɛma: Bɛ yoli yɛlgu refers to how he became chief

- 62. Naa Mahamam Bila: Ʒiri laɣim kɔbga beaten for procession, not danced at gatherings

- 63. Naa Abilabila Saŋmari gɔŋ explanation; other praise names

- 64. Naa Mahamadu: Kulnoli is danced; other names

- 65. the names' uses vary: dancing, praise-singing, processional walking or riding

Other dances from praise-names

- 66. Dam' duu: Tali-Naa Alhassan; meaning of the name

- 67. explanation and story in the name Dam' duu; Tolon-Naa Yakubu's names

- 68. Savelugu-Naa Mahami: Ŋum Biɛ N-kpaŋ

- 69. Kari-Naa Abukari: Zambalana Tɔŋ; the history behind the name

- 70. Diarilana Mahama: Nayiɣ' Naa Zan Bundan' Bini

- 71. commoners also have names that are danced: Salinsaa Bili Kɔbga

- 72. Ninsala M-Biɛ also a commoner's name

- 73. people who are not Dagbamba, such as Bimbila chief

Dances at the Damba Festival

- 74. at Damba Festival, many dances are on display

- 75. the sequence of the Damba Festival

- 76. eighteenth day is final day; greetings and gatherings

- 77. the eighteenth day is wonderful to see

- 78. Dagbamba come from far away to celebrate Damba

- 79. Damba is celebrated at chiefs' houses

- 80. Damba Festival focuses on chieftaincy

- 81. people dance any dance they want at the gatherings

- 82. they dance all the dances mentioned in the chapter

- 83. also Gbunbil' Lɛri: Tugulana Iddi's name

- 84. also Jɛrgu Dari Salima: Gushe-Naa Bukari's name

- 85. also Dɔɣim Malbu: Savelugu-Naa Abukari Kantampara

- 86. also Tibaŋ Taba: Savelugu-Naa Mahami

- 87. also Baŋ Nira Yɛlgu: Kari-Naa Alhassan

- 88. also Naawun' Bɔr Duniya Malgu: Nanton-Naa Sule

- 89. also Ŋun Ka Yiŋa: Vo-Naa Imoro

- 90. also Zamba Kɔŋ Yani: Gushe-Naa Bawa

- 91. also Malimi So: Nanton-Naa Alaasani

- 92. also Kurugu Kpaa: Dakpɛma Suŋna

- 93. also Ninsal' Ka Yɛda: Savelugu-Naa Bukari

- 94. also Kookali: Banvimlana Mahama

- 95. also Pɔhim Ʒɛri: Savelugu-Naa Ziblim

Dances from other tribes

- 96. also many other dances; all these dances can be danced any time if someone wants

- 97. Dagbamba dance dances from other tribes: Yoruba, Kotokoli, Mamprusi, Gonja, and others

- 98. why Dagbamba do not dance Wangara or Mossi dances

- 99. drummers learn the dances because of mingling, especially in Tamale

- 100. how Alhaji Ibrahim learned a Kotokoli dance at a gathering

The benefits of many dances

- 101. dancing helps people become happy when there is sorrow or problems

- 102. people with worries will find their worries reduced

- 103. example: a maalam dancing at his brother's funeral

- 104. dancing and drumming keep people's names alive in memory

<top of page>

The relationship of dancing and drumming; differences in styles of dancing; differences between men's and women's dancing; how people learn dancing; aesthetics of good dancing

Introduction

- 1. overview: the starting of different dances

- 2. dances are not grouped, such as for women or men; drummers beat all dances

- 3. there is dancing at many occasions

Benefits of dancing

- 4. dancing shows happiness; even at final funerals; drumming but no dancing during burial time

- 5. some burials have no drumming; Kulunsi after return to house; praising; dancing at final funeral; exceptions

- 6. dancing especially for old person's funeral; happiness for long life

- 7. dancing and happiness go together

- 8. dancing makes a town good; increases a town's name

Dancing styles and projection of character

- 9. different styles of dancing add to the dance; make it nice, reflect happiness and cool heart

- 10. the dance shows the heart of the person

- 11. dancing with respect; patience and coolness

- 12. different types of dancing reflect different types of human personalities

- 13. showing oneself; project coolness, happiness, and self-respect

- 14. dancing is a choice; what the heart wants

- 15. example: at market show part and hide part of what you sell; or who you are; preserves respect

Dancing movements

- 16. dancing: good to dance coolly, with respect and patience; not roughly

- 17. no particular meaning to movements; try to follow traditional precedents; acknowledge elders

- 18. respect tradition with dress

- 19. good dancers dress dance appropriately to the drumming and the dance itself; don't mix styles

- 20. older people know tradition; dance better than young people

- 21. older people have more knowledge of traditional significance

- 22. experience and knowledge make the dancing nice

Dancers and drummers

- 23. experience: it is good to know the dance and learn it well

- 24. the dancer can follow the beating of the guŋgɔŋ

- 25. dancer can also engage the drummer; drummer can help the dancer

- 26. Nakɔhi-waa originally had movement from drummer; now some other dances

Learning dancing

- 27. can learn dancing from watching and not from asking

- 28. try to dance to resemble an admired dancer one has watched

- 29. when people are dancing, people look at them

- 30. can learn dancing by watching and listening

- 31. styles of movement from the type of dance; some dancers don't have many styles

Dancing of chiefs and commoners

- 32. Damba does not have many styles; movements reflect chieftaincy

- 33. formerly the commoners did not have dance circles as at today's gatherings

- 34. formerly an offense for commoner to dress or dance like a chief

- 35. modern days, the chiefs and commoners are closer

- 36. modern times are good for drummers because life is easier

- 37. people know one another's standing at the gathering place

- 38. when a person dances, drummers show the family; the dance should reflect relationship to ancestors

Dancing of princes

- 39. showing oneself in dancing is not bluffing; but princes don't show themselves

- 40. princes put limits on dances and styles

- 41. different dancing styles for a prince who gets chieftaincy; will not hide

- 42. differences in dancing of chief, commoner, prince

Dancing and styles

- 43. the beating shows which dances have styles, but styles are not as important as dancer's projections

- 44. cool dancing is interesting, but should follow the drums; make the dance look nice

- 45. dancer follows the beating; follows the guŋgɔŋ and all drums together

- 46. drummers can show dancer how to move; makes the dance nicer for everyone

- 47. change dances when drumming changes; different tribes dance with different parts of body

- 48. dancing mainly in the legs; use of arms in Nakɔhi-waa

- 49. Nakɔhi-waa is difficult; sometimes Nakɔhi-waa dancer's arms are just adding movement; Naanigoo is nice without many styles

- 50. drummers adjust beating to individual dancer's movement

Men's and women's dancing

- 51. women also dance in Dagbon

- 52. differences in men's and women's dancing from the body; women more discreet

- 53. woman's body is loose, can move faster; man has more strength

- 54. man dances, turns, and shows smock; women show beauty

- 55. women dance with more shyness; feet in and out; Zamanduniya good for women

- 56. women's arm movements in Damba, Naɣbiɛɣu, Naanigoo; foot movements in Nakɔhi-waa

Dancing and tribal styles

- 57. Damba movements

- 58. Mamprusi dance movements

Conclusion

- 59. dances are different; people call both drummers and goonji groups

- 60. transition to group dances

<top of page>

Baamaaya; Jɛra; Yori; Bila; Nyindɔɣu and Dimbu; Gingaani; dances of the craft-guilds and other tribes; group dances compared to individual dances

Ways to classify Dagbamba dances

- 1. group dances different from individual dances; older; for particular occasions

- 2. Takai, Tɔra, Baamaaya, and Damba are the best-known Dagbamba dances

- 3. Jɛra: only in some towns; for certain types of funerals

- 4. different ways to classify the importance of dances

- 5. importance of Gingaani to chieftaincy; when a chief comes outside his compound

- 6. the important dances are Takai, Damba, Tɔra, Baamaaya, Jɛra; the old dances are Jɛra, Yori, Bila, Nyindɔɣu, and Jinwarba dance

- 7. importance from drumming perspective: Damba, Gingaani, Samban’ luŋa

- 8. everyone knows Takai, Tɔra, Baamaaya; children play them

- 9. children learn Takai, Tɔra, and Baamaaya at an early age

Baamaaya

- 10. nowadays for funerals and festivals; formerly recreational music danced in the night

- 11. danced to escape mosquitoes at night

- 12. original meaning was Daamaaya: the market is cool

- 13. dancing was different; Baamaayaa was Tuubaaŋkpili; current Baamaaya dancers do not know their origins

- 14. this information from old people who were there

- 15. Daamaaya not common; replaced by Tuubaaŋkpilli

- 16. how Daamaaya was danced; in a line with scarves; women also danced it

- 17. Daamaaya dress was jɛnjɛmi, not skirt; women would give the scarves

- 18. Tuubaaŋkpilli dress was piɛto or kpalannyirichoo; replaced by mukuru; Gbinfini-waa (naked dance); use of chaɣlaa

- 19. Daamaaya and Tuubaŋkpilli compared; different dancing and dress

- 20. Daamaaya songs; proverb about fisherman explained

- 21. Daamaaya songs; gossip and abuse; like Atikatika; many chiefs did not like it and forbade it

- 22. Tuubaŋkpilli has become Baamaaya; its songs; other dance beats added like Nyaɣboli

- 23. current Baamaaya dancers do not know the original beating; drummers know it better

- 24. many people do not know this talk about Baamaaya

Jɛra

- 25. old dance; danced at certain funerals: chiefs, old person, relative of Jɛra dancer

- 26. in only a few towns, not everywhere; Changnayili, Jimli are two examples

- 27. Jɛra danced with medicine; need protection; moves inside families

- 28. use of kabrɛ medicine in Jɛra dancing

- 29. dangerous to touch a dancer’s leg; the dance shows strength

- 30. use small guŋgɔŋs and one luŋa; use shakers, saaŋsaaŋ and feeŋa

- 31. Jɛra songs are proverbs; different types

Yori

- 32. for women chieftaincies; danced by Gundo-Naa and Yendi princesses; hold clubs; no singing

- 33. the dance is not common; the beating is the same as when shaving funeral children

- 33. Yori is restricted; not beaten outside its traditional role

Bila

- 33. rare; not in every town; only for some chiefs; examples: Yendi, Yendi Gukpeogu, Tuuteliyili, Karaga, Gushegu, Mion

- 34. use only guŋgɔŋs, but sometimes add drummers

- 35. many medicines used in Bila; dancers show powers and perform wonders

- 36. the wonders: Alhaji Ibrahim has not seen but has heard from others

- 37. knocking a Bila dancer’s leg is forbidden; dangerous; from typical Dagbamba

Other dances

- 38. Bila and Nyindɔɣu not popular for beating; children do not know them

- 39. Nyindɔgu and Dimbu are like Bila; at Yendi Gukpeogu and Gushegu; Nyindɔgu no drums, only songs and hoes; many forbidden things

- 40. Gbɔŋ-waa: barbers’ dance; not beaten by drummers; only on certain occasions

- 41. Gbɔn-waa for funeral of an old barber; sung in the house

Comparing the dances

- 42. these dances are different from Takai, not part of community gatherings; Takai for any occasion;

- 43. dances of eastern Dagbon, many tribes have mixed there; Baamaaya and Jɛra more for western Dagbon

- 44. Yendi side and Savelugu side were separated until Naa Alaasani’s time; dances were also localized

Drummers' knowledge of dances

- 45. drumming talks are many; one can only know one’s extent

- 46. Dagbamba drummers beat dances of other tribes; no tribe can beat Dagbamba drumming

- 47. Dagbamba drummers learn other tribes’ beating to beat for that tribe’s person to dance

- 48. learning is from the heart; Dagbamba have a lot of sense; but not white men’s or soldiers’ beating

Conclusion

- 49. transition to talk of Takai and Tɔra

<top of page>

The Takai and Tɔra dances; their importance in community events

Introduction

- 1. leading Dagbamba dances; old; a pair; dancing must be learned

- 2. basic description of the two dances

- 3. similar beating; Nyaɣboli, Ŋun' Da Nyuli; some songs the same

Tɔra

- 4. the movements are nice; out and back to knock buttocks

- 5. difficult to dance; needs strength; can get hurt

- 6. need to learn Tɔra; young girls learn it in play

- 7. very traditional dance; only women dance it

- 8. women can dance men's dances, but men don't dance Tɔra

- 9. Tɔra widely known among women

Tɔra performance

- 10. Takai and Tɔra danced for occasions; for funerals, or called for a gathering

- 11. Tɔra similar to Takai; funerals, weddings

- 12. Tɔra especially for when shaving the heads of the funeral children, or funeral prayers; beaten at night for four or seven days

- 13. cola and money to call Tɔra as an invitation; what the Tɔra dancers do for drummers; gifts and food

Tɔra's origins

- 14. Tɔra's starting in Samban' luŋa: Naa Yenzoo's wives and elders jealous of his friendship with Jɛŋkuno

- 15. chief's wives lied to accuse Jɛŋkuno of having sex with them

- 16. Jɛŋkuno ran away; Gbanzaliŋ and the chief's wives danced Tɔra

Tɔra's beating

- 17. three dances inside Tɔra: Tɔra Yiɣra, Kawaan Dibli, Nyaɣboli; their songs

- 18. Ŋun' Da Nyuli added; its songs

- 19. Tɔra songs; singing stops as dance heats up

- 20. start beating with Tɔra Maŋa; differences from Hausa Tɔra

- 21. comparing Dagbamba Tɔra and Hausa Tɔra; popularity of Tɔra Yiɣra

- 22. mixed cultural aspects with Hausas; Lua

- 23. Dagbamba are closer to Hausas than to Ashantis

Takai

- 24. danced by Dandawas and Mossis

- 25. Takai not as strong in villages; not mentioned in Samban' luŋa

- 26. old dance, for everyone; Alhaji Ibrahim has not heard any talk about its starting

Takai's importance

- 27. Alhaji Ibrahim telling the truth about Takai; others might tell lies

- 28. example: story about using swords; Alhaji Ibrahim hasn't seen or heard it

- 29. Alhaji Ibrahim is Takai leader; people don't ask how it started; not part of chieftaincy talks

- 30. important but not because of any talk

- 31. continually changes with the generations

- 32. Takai has no talks of its starting; it evolves

Takai drumming styles, drum language, and false meanings

- 33. formerly not many styles of beating the dances

- 34. drummers' styles can be their own idea; no meaning for the dance

- 35. many styles have no language

- 36. compare: drum language important in dances like Baŋgumaŋa and Ʒɛm; more serious than Takai

- 37. no meaning: the beating may reflect or resemble language, but it is not significant

- 38. some styles are talking; some not; “your wrist is sweet”

- 39. some beating styles from the movement of the wrist; fit the beating

- 40. some styles have no intention behind them

- 41. Takai styles are like joking; people can compare to talk

- 42. Takai: important that the dancers knock their sticks on the beating

- 43. Takai song: “knock a person on the head” the main style of Takai

- 44. knocking the head is joking; this style has been there a long time

- 45. guŋgɔŋ follows the dancers; drummers, too; not taught meanings

- 46. Takai's meaning is in its use at gatherings

- 47. how Alhassan taught John false meanings, but Alhaji Ibrahim himself created those styles without language

- 48. anybody can easily compare drumming to language; example: false meanings in Baŋgumaŋa

- 49. example: lumbobli drum language about drink is false; many people talk without knowledge

- 50. no evidence for lumbobli langauge about drink

- 51. need to use eyes and sense to evaluate what people say

- 52. don't follow the talk of people who do not know

- 53. Takai styles are joking; example: Nyaɣboli language

- 54. example: Kondalia language

- 55. example: Kondalia language

- 56. styles come from both language and wrist; anything to energize the dancers

- 57. Takai's meaning is general, from the performance, not the drumming

How Takai evolved to include different dances

- 58. Alhaji Ibrahim met Takai with four dance beats: Takai, Nyaɣboli, Kondalia, Dibs' ata

- 59. dance added to Takai: Ŋun' Da Nyuli

- 60. dance added: Damduu

- 61. dance added: Ŋum Mali Kpiɔŋ

- 62. the process for adding a dance; discuss whether the beating will fit; borrowing dance beats; comparing Takai and Baamaaya

- 63. Alhaji Ibrahim's group added Ŋun' Da Nyuli; not beaten when Alhaji Adam was leading Takai

- 64. how the drummers met and practiced adding Ŋun' Da Nyuli; dancers worked on their own

- 65. the additional dances make Takai more interesting

Beating and dancing Takai

- 66. differences among the Takai dances; the difficulty of the beating

- 67. Takai more strenuous than Baamaaya; danced one to two hours compared to all night

- 68. Takai drummers also use energy to move with the dancers; difficulty of dancing

- 69. Nyaɣboli and Kondalia are difficult; many styles, fast moving

- 70. Takai: more styles in towns than villages; more experience beating it

- 71. not all drummers learn Takai; special groups

Calling Takai

- 72. Takai performance is called; beaten by arrangement

- 73. calling process: send cola and deposit to Takai leader, who calls the group; payment after the dance

- 74. sometimes follow Takai with general dancing; all the money later shared among drummers and dancers

- 75. Takai also for when shaving the funeral children

- 76. not for all funerals or weddings, unless called

- 77. to call Takai needs an event and also a patron

Takai performance

- 78. young drummers beat at venue about 4:00 or 4:30; dance can start if about ten dancers arrive

- 79. fifteen to twenty dancers is optimal, with two guŋgɔŋs and six or seven drummers

- 80. drummers follow the dancers inside their circle

- 81. dancing ends around 6:00; sunset, evening prayers

- 82. for government gatherings, change dances quickly; every five or ten minutes

- 83. slow performance is better; more interesting; fast performance has few dances and changes quickly

- 84. older dancers are better; dance coolly, without confusion

Conclusion

- 85. transition to drumming and dancing at gatherings, especially funerals

<top of page>

Funerals as an example of the role of music in community events; the elder of the funeral house; how a dead body is bathed and buried; the stages of a funeral: three days, seven days, shaving the funeral children, “showing the riches,” sharing property; why Dagbamba like funerals; the importance of funerals; music and funerals

Introduction: funerals

- 1. importance of funerals; many dances; Dagbamba and Muslim funerals are different

- 2. funerals and death: fearful talk

- 3. parts of funeral: preparing the body; the burial; the small funeral: three days and seven days; the final funeral: shaving the funeral children and showing the riches

- 4. other aspects: leader of the funeral takes people through the steps; this talk with regard to an older person who had children

- 5. funerals reflect families: the mother's side and the father's side

- 6. the strength of the mother's house; connection to a child

- 7. the strength of the father's house; father's house performs the funeral before mother's house

Kuyili kpɛma: the leader of the funeral

- 8. “elder of the funeral house”; head of the family; receives all strangers and makes decisions

- 9. must be there before burial; gets the white cloth (kparbu) to wrap the body

- 10. will look at the dead body; inquire about the death

- 11. buy sheep for soli saɣim to feed strangers who gather, sit and sleep outside the house for one week

The Small Funeral

Drumming for the dead person

- 12. drummers beat outside the room where the dead body is; for some people only

- 13. Bɛ kumdi la kuli: “crying the funeral”; taboos: only at funeral house, cannot make a mistake

Bathing the dead body

- 14. two sheep for Limam: one for prayers, one for bathing the dead body

- 15. bathing money; everything in fours for women, threes for men

- 16. burial: four days or three days; guns shoot three or four times

- 17. with inflation, still use numbers that show three and four

- 18. bathing the dead body: tie grass, heat water, everything in threes and fours

- 19. wash with special sponge from tanyibga tree roots; use local soap

- 20. this type of bathing generally not done in modern days

- 21. Muslims says one should use light touch on dead body

- 22. the talk of sponges and soap is from the olden days

- 23. modern people don't even know about it

- 24. Muslim way: Yɛri-Naa, elder who bathes dead bodies; only uses water and hands

- 25. use part of the cloth to make trousers and jumper, hat; wrap the dead body so face is exposed; put in box and bring outside

Settling of debts

- 26. settling debts; funeral elder asks to settle any debts

- 27. someone may have information about debt; will stand and testify

- 28. some debts settled in private

Burial of the dead person

- 29. take body to cemetery; drummers beat Kulunsi

- 30. the kasiɣirba: grave diggers put dead body into grave

- 31. how the kasiɣirba place the body in the grave; uncover face; children must look at parent in the grave

- 32. maalams say looking at sick people makes a person look at himself differently

- 33. therefore others also look at dead people in the grave

- 34. formerly children were forced to look; helps people live better lives

- 35. only those at the burial look; no delay for the burial

- 36. burial generally the same day a person dies, or the next day

- 37. people rush to funeral house; nobody waits or delays

- 38. even the funeral elder does not delay; if delayed, an elder from the area will fill in

- 39. townspeople use cemeteries; in villages the grave is inside the compound, marked with cowries

- 40. chiefs are buried in their room, which is then closed off

- 41. some people buried in compound, some in room; sometimes funeral elder will stay and live in the house

- 42. if person buried in bush, will mark the grave; then return to funeral house

- 43. return to house for prayers; pass woven pan (pɔÅ‹) for burial money

- 44. burial money is any amount people give to help with expenses

Prayers and sacrifice: the “three days” and the “seven days”

- 45. alms of small foods like maha given to children

- 46. people stay at funeral house for one week to console family

- 47. bɔɣli lɔɣbu: covering the hole; the three days and the seven days

- 48. slaughter a sheep: shared to kasiɣirba, drummers, Limam

- 49. prayers and alms on the pɔŋ; repeated on the seventh day

Kubihi pinibu: shaving the funeral children

- 50. shaving the funeral children; usually only for chief's children at the small funeral

- 51. shaving is for all the family

- 52. shaving is optional, but most do it to show relationship

- 53. “buying your hair”: pay the barber but don't shave

- 54. how the relatives sit to be shaved; drummers beat same beating as Yori; not grandchildren

The grandchildren's role

- 55. beating ground with sticks; collecting money; the bereaved playmates

- 56. grandchildren sometimes dance Dikala; drummers also praise people

Conclusion of the small funeral

- 57. on the seventh day, the elder of the funeral sets date for the final funeral; some months later

- 58. after small funeral, then the mother's house funeral

- 59. elder of the funeral leaves, but will help provide for widows and children

The final funeral: kubihi pinibu, buni wuhibu, and sara tarbu

- 60. final funeral: shaving the funeral children; kill cow; bathe the eldest son and eldest daughter

- 61. one week later: showing the riches and giving the sacrifice; Thursday and Friday are strong; people gather at funeral house

- 62. showing the riches: in-laws; husbands of the dead person's daughter; gifts of cloth, scarf, waistband, cola, and sacrifices

- 63. public presentations by the in-laws; the role of Zoɣyuri-Naa

- 64. in-laws bring drummers and dance groups

- 65. dancing in the night; happiness

- 66. recapitulation: the work of drummers at the small funeral

- 67. the drumming and dancing at the final funeral

- 68. adua and sara tarbu: prayers and sacrifice the next day to finish the funeral; then share the property

Funerals before Islam

- 69. funerals before Naa Zanjina: buli chɛbu; burial and then sacrifice a goat; “knocking out”

- 70. Naa Zanjina brought maalams to show how to bath and bury a dead person

Benefits of funerals: knowing the family and the friends

- 71. help to make the family well; get to know one another

- 72. get to know your mother's side

- 73. when take friends and family to wife's parent's funeral, gives great respect

- 74. learn about relationships you might not know about

- 75. if the family is small, some will attend funeral with many friends

- 76. how your friends will support you, including even their friends who don't know you

- 77. how funerals become large; example of someone with many children and grandchildren

- 78. benefits of funerals: know the family and know the friends

- 79. problem of funerals: when food is not enough, some only so the small funeral

- 80. somebody may profit from funeral from gifts of food

- 81. Dagbamba reciprocate with regard to funerals

Drummers' work at funerals

- 82. show the family to one another; spending on drummers adds respect

- 83. the in-laws bring different dances to the funeral house; dance group members support one another and their friends

- 84. drummers also have several dance circles

- 85. friendship the basis for all the help with dances; go and return home; Simpa and Baamaaya all night

- 86. the dance groups are not paid; only come to help their friends

- 87. like paying a debt of friendship; reciprocate and help one another; Dagbamba way of living

- 88. resembles talk of respect: how Dagbamba help one another; how drumming talks enter Dagbamba way of living

Why attending funerals is important for the family

- 89. a father tells daughters' husbands that they should perform his funeral well; adds respect to wife

- 90. if many friends attend a funeral, the family may give one of them a wife; friendship brings family

- 91. a well-attended funeral adds to a family's respect

- 92. sometimes people attend funerals because of the dead person who has attended funerals; Alhaji Ibrahim like that

- 93. people do not attend funeral of someone who did not attend funerals; taboos

- 94. not attending funeral or sending a messenger is like removing oneself from the family

- 95. important funeral for someone without children; fear and respect; taboo

- 96. funerals have not changed; deeply linked to family life and family strength

- 97. great respect if Yaa-Naa sends a messenger to a funeral

Conclusion

- 98. transition to talk of chiefs' funerals and maalams' funerals

<top of page>

How Muslims are buried; stages of a Muslim funeral; sharing property; how chiefs die; how chiefs are buried; the installation of the Regent; chiefs funerals and the work of drummers; example: Savelugu; the Gbɔŋlana and the Pakpɔŋ; seating the Gbɔŋlana; the Kambonsi; Mba Naa and showing the riches; selection of a new chief

Introduction

- 1. differences of Muslim funerals; drummers do not beat

- 2. differences among Muslims: those who only pray and those who are more deeply inside

Muslim funerals

- 3. three days and seven days; can extend time for strangers; finish with the forty days; no showing the riches

- 4. prayers of the dead body in the house and at burial

- 5. gather in evenings for prayers and preaching, throughout

- 6. for maalam or important Muslim, many maalams will come and preach

- 7. final day preaching until daybreak; contributing money and alms; money for maalams; greetings; same prayers at forty days

The forty days

- 8. widows stay inside the house for the forty days

- 9. bathing the widows; prayers and alms; return to family house; some may remain to care for children

Sharing the property among Muslims

- 10. in Dagbamba funeral, can share after showing the riches, but often delay until later

- 11. Muslims share property on the forty days gathering; a maalam shares according to Holy Qur'an; a woman gets one half of man's share

- 12. how property is divided among the widows and children

- 13. property given before death is not counted as a share

- 14. while living, some people give property to brothers' children living with them; otherwise excluded when sharing property at funeral

- 15. written wills can be challenged; people trust maalams; a child can only be excluded when person was alive, not after death

- 16. sharing property is difficult; complexities of a large estate

- 17. Holy Qur'an gives general guidelines for maalams to follow; no specific bequests

Sharing the property in Dagbamba villages for non-Muslims

- 18. typical Dagbamba who are not Muslims; more differences

- 19. in Dagbamba villages, the elder of the funeral takes the property of his brother; also takes care of the children

- 20. in villages, the children will group and give seniority to the eldest brother

- 21. how the house can break up; issues among children of different mothers

- 22. sometimes the household will be unified

Sharing property in the towns

- 23. dividing versus selling a house in the towns

- 24. trouble common among the brothers' wives and children

- 25. example: Alhaji Ibrahim and his brother Sumaani and house in Tamale

- 26. difficult for siblings from different mothers to stay together in a house

Transition

- 27. conclusion of Muslim funerals; no drumming; chiefs' funerals have many talks

- 28. different drumming for different types of people; chiefs are different

Chief's burial and small funeral

- 29. drumming: crying the funeral when dead body in the room; not taught

- 30. chief “does not die“; dress the chief and walk him to the grave

- 31. beating Gingaani for big chiefs; placing the body in the grave; drumming for three days and seven days to finish the small funeral

- 32. deciding about the shaving day and seating the Gbɔŋlana

Example: Savelugu chief's small funeral and seating of Gbɔŋlana

- 33. this talk also about chieftaincy; Savelugu the main chief of western Dagbon (Toma)

- 34. Nanton-Naa performs Savelugu-Naa's funeral

- 35. Yaa-Naa's elders meet Nanton-Naa; Namo-Naa sends elders; Yendi Akarima

- 36. seating Gbɔŋlana after the small funeral; shaving the funeral children

- 37. drummers wake up the funeral on Friday; Kambonsi also come

- 38. shave the Pakpɔŋ and Gbɔŋlana first

- 39. then shave funeral children; drummers beat Yori

- 40. slaughter cow; how it is shared; head to Namo-Naa's messenger; legs to Akarima

- 41. Gbɔŋlana wears “red-day dress“; he and Pakpɔŋ wear hat called buɣu

- 42. Namo-Naa's messager leads Gbɔŋlana outside with Gingaani

- 43. message of the Gbɔŋlana; the chief has not died

- 44. maalams say prayers; after, drummers beat Zuu-waa for the Gbɔŋlana and Pakpɔŋ

- 45. Gbɔnlana will sit in place of chief until final funeral; acts in his place

Example: Savelugu's chief's final funeral, waking up the funeral

- 46. many chiefs come with drummers; bring food; drummers wake up the funeral; Kambonsi

- 47. the Kambonsi: not at every funeral; differences for women and men

- 48. Kambonsi gather and go around the chief's house; dance Kambɔŋ-waa

- 49. Kambonsi can attend a commoner's funeral for pay

Example: Savelugu chief's funeral, showing the riches

- 50. Mba Naa kills the chief's horse and dog

- 51. elders eat blood-soaked cola; meat thrown into wells

- 52. chiefs and Gbɔŋlana ride horses; daughters wear kpari; Pakpɔŋ carries calabash around her neck

- 53. drummers beat; procession around the chief's house three times

- 54. Gbɔŋlana and Pakpɔŋ gather with Nanton-Naa outside the house

- 55. cows and cloths from Gbɔŋlana's mother's house and husbands of Pakpɔŋ and other daughters

- 56. many animals at Savelugu chief's funeral

- 57. not all the cows are slaughtered at chief's house; many used for food for visitors

- 58. dancing in night; next day prayers and alms; funeral children to Nanton and then to Yendi

Choosing a new Savelugu-Naa

- 59. Nanton-Naa sends messenger with Gbɔŋlana to greet Yaa-Naa that funeral is finished; Yaa-Naa will choose new chief

- 60. many chiefs want Savelugu, along with Gbɔŋlana and other princes

- 61. other who claim Savelugu to interfere

- 62. Yaa-Naa informs Namo-Naa of his choice; the drummers gather at Yaa-Naa's house

- 63. Namo-Naa sings praise-names for the chiefs

- 64. Mba Duɣu announces the selection

- 65. putting the gown on the new chief; Namo-Naa beats Ʒɛm; sharing cola

- 66. as the candidates leave Yendi, they greet Yaa-Naa in case of another chieftaincy

- 67. if Gbɔŋlana does not get Savelugu, will be given another chieftaincy

- 68. Gbɔŋlana and funeral children greet Yaa-Naa; follow new chief back to Savelugu

- 69. conclusion of the talk

<Home page>

<Home page>