A Drummer's Testament: chapter outlines and links

<Home page>

<Home page>

Volume I: THE WORK OF DRUMMING

Part 4: LEARNING AND MATURITY

Chapter titles above go to chapter outlines on this page.

Chapter title links in the outline sections below go to chapter portals.

Outline section links go to web chapter sections.

<top of page>

Volume I Part 4: Learning and Maturity

Types of toy drums for children; first proverbs; how a child is taught to sing; discipline; children who are “born” with the drum; a child who was trained by dwarves; learning the chiefs; learning to sing; performing; how young drummers respect their teachers; obligations to teachers; teaching and learning

Introduction

- 1. transition to other talks of drumming

Drumming and family

- 2. drumming moves through family

- 3. a drummer's son not forced to drum, but one son of a daughter must drum

Training a young child

- 4. how a drummer beats his drum when his wife brings forth

- 5. at three or four years old, child gets giŋgaɣinyɔɣu, a small drum, to play; no training

- 6. by six to eight, gets lunnyiriŋga, smaller than lumbila; begins to learn

- 7. accompanies drummers; carries drums; picks up money given to drummers and dancers

- 8. begin teaching with Dakɔli n-nyɛ bia and Namɔɣ' yil' mal' k-piɔŋ

- 9. by twelve or thirteen, has used sense to learn what the drummers beat and sing

- 10. the child learns his own family line and praises

- 11. from the child's grandfathers to father; will learn in six months to a year

- 12. young drummer goes in night to other drummers to learn more; praise songs; presses his teacher's legs

- 13. some children do not need much teaching

- 14. some children do not learn well; knocked with drum stick

- 15. formerly, more forcing to learn; more serious; now people less willing to suffer

- 16. Alhaji Ibrahim trained by Lun-Naa Iddrisu and Mba Sheni; how Sheni talked to him

Training by dwarves

- 17. child can be trained by dwarves; example: Namɔɣu-Wulana Zakari

- 18. how Zakari was lost in the farm

- 19. the search for Zakari; the soothsayer's advice; the funeral of Zakari

- 20. Zakari found eight months later in the farm; would not speak

- 21. medicine man treated Zakari; Zakari singing; he said he was kept by dwarves in a hole

- 22. Zakari a great drummer and singer; never tired; different from other drummers

Teaching young drummers

- 23. at fourteen to sixteen, get lundaa; begin learning Jɛŋgbari bɔbgu

- 24. the meaning of Jɛŋgbari bɔbgu

- 25. the proverbial names of the Yendi chiefs

- 26. next learn the chiefs of other towns like Savelugu, Mion, and so on

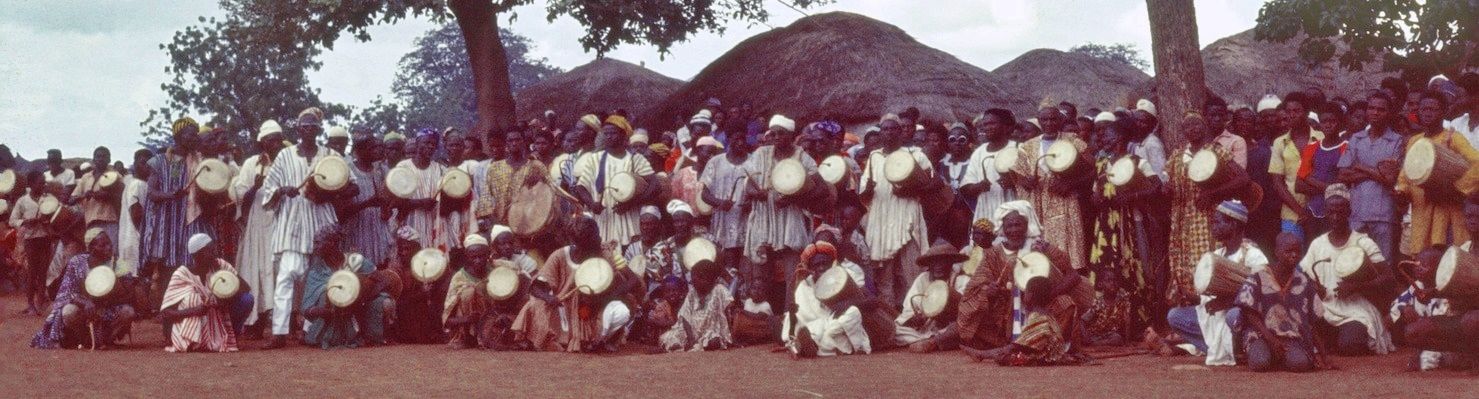

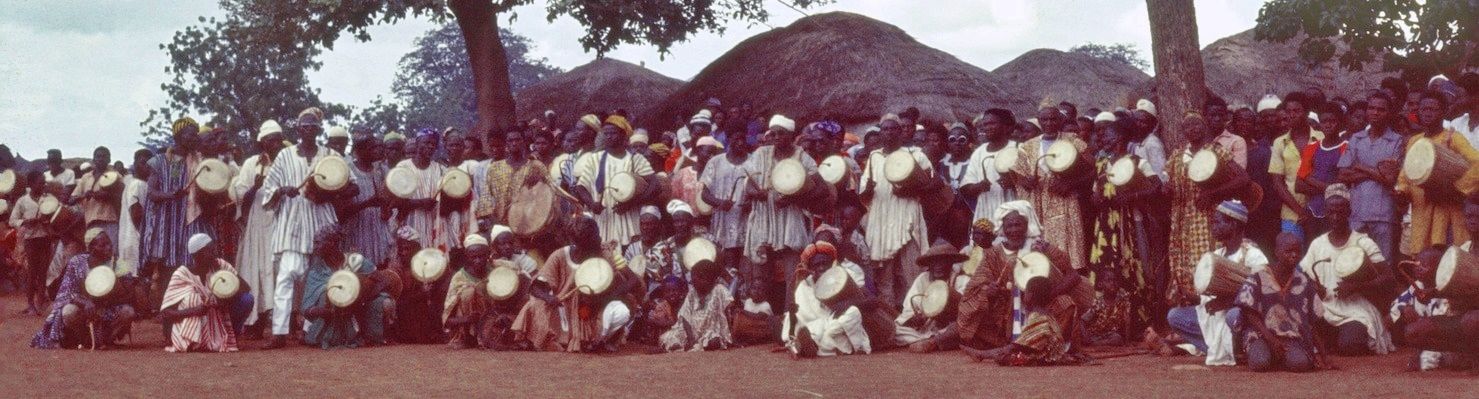

- 27. how the young drummers demonstrate the extent of their knowledge

- 28. should learn both to sing and to beat the drum

- 29. from sixteen to eighteen is when he can learn and retain knowledge

Singing

- 30. young child must continue to sing through puberty or his voice will reduce

- 31. singing voices are different; voice should be clear that people hear and understand

- 32. how drummers work to improve singing; also use medicine

- 33. not all drummers know singing or people's lines; but must know beating

Learning comes from the heart

- 34. someone who has no interest doesn't learn well

- 35. some drummers cannot beat on their own; need others to beat

- 36. need patience and interest to learn; learning is in the heart

- 37. must hear the sound of the drum; think about how the sound is coming

Traveling to towns to learn from other drummers

- 38. by twenty-one or twenty-two, learn to the extent of beating Samban' luŋa; may or may not perform

- 39. go around to towns to learn from different drummers; differences in knowledge

- 40. stay in drummer's house; farm and work for him; learn in the night

- 41. to learn about some chiefs or some talks requires animal sacrifices

- 42. when go to another drummer, act as if do not know; only add his knowledge

- 43. some drummers only teach; some use lundaa to teach

The importance of being taught

- 44. some drummers do not go around to learn; only use their sense; comparison to Baamaaya drummers

- 45. someone who was taught is better than someone using sense to beat (self-taught)

- 46. beating with sense cannot go far; but someone who was taught can add sense

- 47. the one who was taught knows the ways of drumming; limitations of the one beating with sense

Beating the different sizes of drums

- 48. drummers can only learn their extent; compared to their progression among different drums

- 49. comparing the different drums for praising

- 50. drummers choose and get used to the drum they like to beat

- 51. someone who beats lundɔɣu cannot beat lundaa the same way; lundɔɣu seems heavy to a lundaa drummer; lundaa and lumbila need more energy

Developing into maturity

- 52. can learn singing; personal styles of the voice comparable to styles of drumming

- 53. people show different sides of themselves when drumming or singing

- 54. no charge when going around to learn; give gift when finished; share the benefits

- 55. need patience to learn; don't hurry; learn drumming well to receive the benefits of drumming

- 56. the responsibilities of teaching; need to continue learning

<top of page>

Why Dagbamba learn other tribes' drumming; the difficulty of learning the Dagbani language; the drumming styles and dancing of: Mossis, Kotokolis and Hausas (Jɛbo, Gaabitɛ Zamanduniya, Mazadaji, Adamboli), Bassaris and Chembas and Chilinsis, Dandawas, Wangaras, Gurumas, Konkombas, Frafras, Ashantis, Yorubas; differences in the drummers from different towns

How Alhaji Ibrahim traveled to learn more

- 1. dances of the tribes: learning from experience and not from training

- 2. Alhaji Ibrahim has learned many dances

- 3. should beat without changing; otherwise make mistakes

- 4. Alhaji Ibrahim trained in Dagbon and traveled to the South; some dances only beaten in South; guŋgɔŋ has different ways

Dagbamba drummers' knowledge compared to other tribes

- 5. Dagbamba beat the dances of other tribes; other tribes cannot beat Dagbamba dances

- 6. Dagbamba drumming difficult for others; examples

- 7. this ability makes others wonder; another example

- 8. speculate that drumming is difficult because Dagbani is difficult

- 9. comes from intelligence and experience; differences among Dagbamba drummers; example: Dakpɛma's drummers don't travel

- 10. comes from being trained as a foundation before experience

Mossi dance and guŋgɔŋ beating

- 11. example: Mossi dance; Alhaji Ibrahim watched and learned the different drum parts; important to notice differences; Mossis and Yarisis

- 12. example: Alhaji Ibrahim can beat Mossi language clearly without understanding it

- 13. have to adjust beating to the other tribe; example: beating guŋgɔŋ to resemble Mossi drumming

- 14. Alhaji Ibrahim's learning is different from many other Dagbamba drummers; knows the differences

- 15. different ways to hold guŋgɔŋ; the sound is important for correct beating

- 16. example: compare Jɛblin beating Gbada with a drummer who added Dagbamba styles; fit the sound but were not correct

- 17. importance of learning work well; example: how Alhaji Ibrahim beats Kotokoli dances

Jebo

- 18. example: in South, beating Jebo for a Kotokoli princess

- 19. Alhaji Ibrahim accurately beat Jebo drum language styles; people questioned him

- 20. how the Kotokoli drummer asked Alhaji Ibrahim where he learned Kotokoli beating

Zamanduniya

- 21. beaten differently for Dagbamba and Kotokolis (Gaabiti), because of language

- 22. Hausa form of Zamanduniya is different: Hankuri Zamanduniya

- 23. Dagbamba form is Ayiko; only some drummers know the differences in all three

- 24. Zamanduniya brought to Dagbon by Alhaji Adam Mangulana; not an old dance

- 25. Ayiko was there when Alhaji Ibrahim was a child; how Alhaji Mumuni and Sheni used to beat drums in the market

- 26. the name of Ayiko has been absorbed into Zamanduniya; only old drummers know it

- 27. many styles in Zamnaduniya; Alhaji Ibrahim knows the differences and can beat them clearly

- 28. to beat it correctly, the drum and the guŋgɔŋ have to answer one another

Adamboli

- 29. Dagbamba heard it from Hausas first; originally Kotokoli; Hausas beat it without guŋgɔŋ

- 30. Alhaji Ibrahim's group beatsa it the same way ass the people whose dance it is

- 31. Ŋun' da nyuli styles can fit well inside Adamboli, but a mistake that spoils Adamboli

Other tribes

- 32. Bassaris are close to Kotokolis; have lunsi drummers; Alhaji Ibrahim learned in Accra; taught Tamale drummers to beat it

- 33. Chilinsis use only guŋgoŋ; Alhaji heard it ansd taught Tamale drummers

- 34. Zambarima dance: Alhaji Ibrahim learned it in Kumasi and Accra; also for Dandawas, beat Gbada

- 35. Wangaras and Ligbis: Kurubi; Wangara dance at Kintampo during Ramadan for unmarried girls; young men hire drummers

- 36. how the girls dress and dance; one has to travel to see it

- 37. Gurunsi dance: Alhaji Ibrahim learned it at Kumasi and Kintampo

- 38. Konkomba dance: Alhaji Ibrahim learned it in Yendi; description of the instruments and the scene

- 39. how Alhaji Ibrahim brought the Konkomba dance to Tamale and showed how to beat it

- 40. Frafra, Ashanti, Gurunsi dances: watch them and learn how they beat

- 41. no other tribe can beat Dagbamba dances, not even Mamprusis; Dagbamba beat their dance

- 42. Kusasis don't use drums, so Dagbamba don't beat their dance, but beat Damba for them

Learning: training and experience

- 43. Alhaji Ibrahim's group always knows how to beat for any dancer; from traveling and learning

- 44. learning the easy parts of drumming; learn the ways of different places, know how they change; follow the local styles

- 45. once you learn something so that it is easy, it is not difficult to learn other ways of doing it; need to travel

- 46. learn from somebody who knows it well, then travel and use sense to add

- 47. John is learning drumming like that

Conclusion

- 48. transition to talk of drumming eldership and chieftaincies

<top of page>

The origins of drum chieftaincies; drum chiefs and chieftaincy hierarchies; the different drum chieftaincies of the towns; how a chief drummer is buried; how a drummer gets chieftaincy; chieftaincy and leadership

Introduction

- 1. introduction: burial of a chief drummer; drum chiefs in Dagbon

- 2. chieftaincy is leadership; increases respect in a group; drum chieftaincies began long ago

The origins of drumming and the chieftaincy of Namo-Naa

- 3. Bizuŋ the son of Naa Nyaɣsi; Bizuŋ's children are the line of drummers; drummers' grandfathers are Naa Nyaɣsi, Bizuŋ, Ashaɣu, the line of Namɔɣu; Kosaɣim the line of Savelugu

- 4. Namo-Naa the chief drummer of Dagbon

Hidden talks about chieftaincy descent

- 5. a hidden talk: people say Bizuŋ was Namo-Naa but the chieftaincy itself had not started

- 6. chieftaincy talks: people call all Yaa-Naas as fathers or children of Yaa-Naas

- 7. Naa Nyaɣsi's “children” whom he made chiefs in tindana towns were not all his real children, but they are called his children; if a chief has no children, drummers call his sister's or brother's child the chief's son; even Yaa-Naas

- 8. Namo-Naa the father of all drummers, and Namo-Naa is the line of Bizuŋ; but not all Namo-Naas are actual children of the line of Bizuŋ; Bizuŋ and other early drummers were not chiefs, but they are called Namo-Naa; one's child is the one who does one's work

- 9. the difficulties of old or hidden talks, the secrets of drumming regarding the names and identities; people who have written about Dagbon do not know it

- 10. early Namɔɣu chiefs were not drumming chiefs as they are today; chieftaincy has evolved

- 11. example from Naa Luro's Samban' luŋa: drummers did not go with Naa Luro to the war

- 12. Bizuŋ and his children were there as drummers; gradually increased their presence

The Lun-Zoo-Naa chieftaincy

- 13. different from Namo-Naa; now only in Gukpeogu and Karaga

- 14. relationship of Lun-Zoo-Naa to Bizuŋ; possible Guruma connection

- 15. Lun-Zoo-Naa chieftaincy is older than Namo-Naa chieftaincy

- 16. the seniority of Namo-Naa over Lun-Zoo-Naa; Namo-Naa from Yaa-Naa's line

- 17. the relationship of Namo-Naa and Lun-Zoo-Naa

- 18. drumming chieftaincies are old but not as old as Dagbon; drumming itself is older; many differences among the towns

Standard order of drumming chiefs

- 19. most towns drumming chiefs: Lun-Naa is first, then Sampahi-Naa and Taha-Naa; then differences among chiefs following: Dolsi-Naa, Dobihi-Naa, Yiwɔɣu-Naa

- 20. examples of different ordering of drum chiefs in chieftaincy

hierarchies at Nanton (Maachɛndi, Lun-Naa, Sampahi-Naa, Yiwɔɣu-Naa, Dolsi-Naa,

Dobihi-Naa, Maachɛndi Wulana), Savelugu (Palo-Naa, Lun-Naa, Sampahi-Naa,

Dolsi-Naa, Taha-Naa, Yiwɔɣu-Naa, Dobihi-Naa, and Palo-Wulana)

- 21. Lun-Naa not always senior; examples: Kumbungu, Nanton, Gushegu, Karaga, Mion

The position of Namo-Naa

- 22. Yendi has many drum chiefs because Yendi elders have drum chiefs; examples: Mba Duɣu, Kuɣa-Naa, Balo-Naa, etc.; all follow Namo-Naa

- 23..the position of Namo-Naa and Yendi Sampahi-Naa; the respect of Namoɣu Wulana

- 24. the relationship of Zɔhi Lun-Naa and Namo-Naa chieftaincies

- 25. Namo-Naa only beats drum for something important involing Yaa-Naa; Namo-Naa has his house drummers to represent him or stand for him

- 26. all drummers look at themselves as children of Namo-Naa; drummers have no set town; formerly would follow chief who gave a drum; if have own drum, can follow any chief; drumming and traveling

How drum chiefs move from town to town

- 27. Drummers follow chiefs; a chief can call a drummer to follow him as he moves from town to town

- 28. drummers don't have towns; example: Karaga Lun-Naa Baakuri from Savelugu drum chiefs

- 29. drumming chieftaincies follow two things: family line and chiefs

- 30. how drummers follow chiefs; example: Tamale Dakpɛma Lun-Naa's line from Yendi; leaving other Dakpɛma Lun-Naas' family

- 31. example: Dakpɛma Taha-Naa from Karaga Lun-Naa Baakuri's line

- 32. if a town's drummers challenge a drummer brought from another town, the drummer can show how all their families came from other towns; all are children of Namo-Naa, every town is their town

How drummers move into drumming chieftaincies: olden days

- 33. drummers can get a chieftaincy by following and greeting a chief

- 34. some chieftaincies follow family door; if a drum chief dies, others will move up, and son will get a smaller chieftaincy

- 35. if sitting drum chiefs quarrel over an open chieftaincy, chief can move the dead chief's son directly to the position

- 36. drum chiefs are not removed; example: only current Naa Yakubu has removed drum chiefs along with removing towns' chiefs; Dagbon chieftaincies are spoiled

- 37. how Namo-Naa Issahaku was removed

- 38. how a Namo-Naa must visit ancient Namɔɣu near Yaan' Dabari

- 39. in olden days, a new drumming chief only is a chief drummer died; chiefs were not removed

How a Namo-Naa is buried and a new drumming chief installed

- 40. two ways to drum chieftaincy by chief who wants a drummer or by family door; join talk to drum chief's death, burial, and succession

- 41. a drummer is buried with a drum, broken stick, and skin; Namo-Naa buried with drum covered with leopard skin; burial dress and procedures resemble Yaa-Naa; Namo-Naa lies on skins of animals; the dead body is walked to the grave

- 42. walking to the grave also for chief drummers of major towns; example: also Savelugu, Gushegu, Karaga; Yelizoli

- 43. after Namo-Naa's funeral, Namo-Naa's elders tell Yaa-Naa whom they want; if Yaa-Naa agrees, the new Namo-Naa is given chieftaincy in same room Yaa-Naa becomes a chief; walking stick, gown, timpana, guns

The installation of a Palo-Naa

- 44. other towns' drummers follow family doors; example: Savelugu Palo-Naa; the starting of two Palo lines

- 45. usually they inherit according to family; Palo-Naa succeeded by the next chief from his line

- 46. how Savelugu drummers will talk to the Savelugu chief; cola sent to the new chief

- 47. the drummer's gather after the funeral; Palo-Naa Gbɔŋlana will sing resembling Samban' luŋa; walking on knees

- 48. how Savelugu-Naa will greet the Gbɔŋlana and Pakpɔŋ; sharing cola

- 49. giving gown to the new Palo-Naa; the advice the chief gives

- 50. removing the buɣu from the Gbɔŋlana; Gbɔŋlana given a wife

How Alhaji Mumuni refused drum chieftaincy

- 51. formerly, drummers were not buying chieftaincy; chiefs feared taking drummers money; chiefs called drummers for chieftaincy and gave drummer a house, horse, stableman, wife, and household support; but modern chiefs want money

- 52. Alhaji Mumuni's refused chieftaincy because of his commitment to Muslim religion

- 53. how Alhaji Mumuni refused chieftaincies in Voggo, Gushie, Lamashegu, Pigu, Savelugu

- 54. example: when Nanton-Naa Alaasambila was chief of Zugu, story of how Mumuni refused chieftaincy calls but had to visit Zugulana because of his wife was Zugulana's sister

- 55. before the Friday gathering, Zugulana planned with Zugu-Lun-Naa to offer Mumuni a gown and an additional wife

- 56. Mumuni did not know the plan; the chief's sitting hall filled with people; Zugulana said he had caught Mumuni for chieftaincy; Zugulana's proverb to Mumuni

- 57. how the Zugulana spoke to Mumuni; how Mumuni refused in front of all the people; Zugu Lun-Naa confesses the plan to Mumuni

- 58. how Mumuni told Alhaji Ibrahim the story

- 59. Mumuni's story with Zugulana an example of how drum chieftaincies were formerly given; Zugulana continued to ask Mumuni even after he became Nanton-Naa

How drum chieftaincies are bought in modern times; rivalry over chieftaincy

- 60. former chieftaincy customs compared to exchange of respect

- 61. in drumming chieftaincy lines, people recognized seniority

- 62. payment and bidding from additional competition within families; how princes buy chieftaincy

- 63. modern drum chieftaincies are bought, the same as how princes buy chieftaincy

- 64. some chiefs even announce the price for the drum chieftaincy that has fallen

- 65. modern times, some drum chieftaincies are not bought, if a chief wants a certain drummer

- 66. some drummers who pass over senior drummers to eat chieftaincy are attacked with medicines

- 67. jealousy and rivalry; drummers pray to take a chief's position

- 68. Alhaji Ibrahim does not want chieftaincy; he is qualified, but he doesn't want troubles

Drum chiefs' responsibilities and need for support

- 69. not all drummers become chiefs; Alhaji Ibrahim has family door but does not want chieftaincy; chieftaincy has responsibilities; need the help of brothers and children; example: Namo-Naa has many people to send in his place

- 70. a drum chief has people behind him; some drum chiefs cannot drum well or sing well; some are aged; they have children or grandchildren who can do the work; example: Nanton Lun-Naa Iddrisu is very knowledgeable but very old; Nanton Sampahi-Naa Alidu does the work of Lun-Naa and Maachɛndi

- 71. Alhaji Ibrahim not a drum chief but has more respect than many chiefs; Alhaji Mumuni the same; Savelugu young men's drum chief (Nachimba Lun-Naa Issa Tailor) and the young drummers all follow Mumuni as their leader

- 72. the same in Tamale with Alhaji Ibrahim; how Alhaji Ibrahim calls drummers from other towns for wedding and funeral gatherings

- 73. why Tamale does not have Nachimba Lun-Naa; Tamale drumming leadership from Alhassan Lumbila, Mangulana, Sheni Alhassan, and Alhaji Ibrahim; based on respect and not chieftaincy

- 74. how Alhaji Ibrahim leads: the Tamale drummers gather at his house and follow Alhaji Ibrahim; he receives cola, assigns drummers to different houses, shares money; chieftaincy is in his bones

- 75. Alhaji Ibrahim work as leader of Tamale drummers; because of his respect and knowledge; his position compares to chief of drummers

<top of page>

How drummers earn money at gatherings; example of Namo-Naa and his messengers; sharing money to elders; “covering the anus of Bizuŋ”; how Alhaji Ibrahim divides drummers into groups and shares money; why drummers share money to old people and children; what drumming doesn't want; the need for “one mouth”

Introduction

- 1. Introduction: sharing of money based on seniority and chieftaincy

Example: how Namo-Naa's messengers attend a Savelugu chief's funeral

- 2. Namo-Naa sends messengers to Palo-Naa; drummers beat to start funeral; Palo-Naa separates Namo-Naa's share

- 3. Thursday showing the riches; more drumming and money; Namo-Naa has a share

- 4. Friday prayers; praise drumming; more money shared

- 5. sharing the funeral cows: some for Yendi people; some for feeding; some for visitors

- 6. some cows for food; others are sold or taken home

- 7. drummers beat when funeral cows are slaughtered at chief's house; drummers get the heads; Palo-Naa gives to Namo-Naa's messengers

- 8. only the heads from the slaughtered cows; not the gift cows

- 9. Namo-Naa's messengers give some of the heads back to Palo-Naa; return to Yendi with money and cowhead

- 10. Namo-Naa will share everything with the drum chiefs of Yendi

What Namo-Naa gets

- 11. money and meat from funerals or wherever drummers go; also from people looking for chieftaincy

- 12. Namo-Naa's messengers at funeral, go around and greet chiefs, also receive greetings for Namo-Naa

Savelugu Palo-Naa

- 13. Palo-Naa does not get the amount Namo-Naa gets

- 14. Dolsi-Naa, Taha-Naa, and Dobihi-Naa a different door

- 15. how Palo-Naa has to share with other drummers

- 16. how Savelugu youngmen's drummers share with elders

- 17. Namo-Naa gets more than Palo-Naa because of people greeting Yaa-Naa for chieftaincy

Example: Nanton drummers at a village chief's funeral

- 18. how Nanton drum chiefs attend the funeral of a village chief

- 19. beating drums when shaving the heads

- 20. barbers and drummers share the money

- 21. seating the Gbɔŋlana

- 22. dancing; summary of the money received

- 23. sharing the money among the drum chiefs

- 24. money reserved for sick or excused drummers

- 25. money reserved for daughters of drummers

- 26. the drum chiefs share the money

- 27. how they share the cowheads and sheepheads

- 28. why there are many animals at a village chief's funeral

Tamale: Alhaji Ibrahim and the young men's drummers

- 29. how Alhaji Ibrahim organizes drummers for different wedding houses; greeted with food

- 30. how drummers earn money at wedding houses; more food before leaving

- 31. differences when perform with dancers as a cultural group; dancers get their share

- 32. normal way: the groups bring their money from the different weddding houses

- 33. sharing depends on work: elders who identify people's praise-names, singer, lundaa, guŋgɔŋ

- 34. elders, singer, lundaa get larger shares; others get less; share even to children who collect money

- 35. shares for the old drummers who do not beat, whether or not they went to the wedding house

- 36. add for a drummer who has a naming or a funeral to perform

- 37. drummers share the money at home to sisters and elders; covering the anus of Bizuŋ

- 38. sharing a little to children in the house

The ways of sharing

- 39. accept even nothing, even from an empty hand; covering Bizuŋ's anus

- 40. knowledge about sharing is from the elders; sharing has restrictions

- 41. how drummers steal money; such a drummer will not advance

- 42. drummers leave money in open; afraid to steal

How Alhaji Ibrahim became responsible for the Tamale drummers

- 43. when Sheni was leading, he gave the sharing to another drummer who stole and became unable to sing

- 44. how a voice can decrease: by not singing through puberty or by stealing

- 45. how Sheni gave the sharing to Alhaji Ibrahim; twenty-five years and no quarrels

- 46. how Alhaji Mumuni told Alhaji Ibrahim not to share the money; what happpend

- 47. how the drummers asked Alhaji Ibrahim to share the money; the lesson of Alhaji Mumuni

Conclusion

- 48. the money from drumming is not consumed alone; shared among many people

<Home page>

<Home page>